Yikes

SAWHORSE

From Architecture Focus newsletter:

(Sundry Photography/Shutterstock)

In a recent article in The New York Times, Anna Kodé lamented the blandness of multifamily architecture in the U.S. and posited several theories for this disappointment.

The root cause of the banality is quite simple. The answer is something that, once seen, cannot be unseen: stairs.

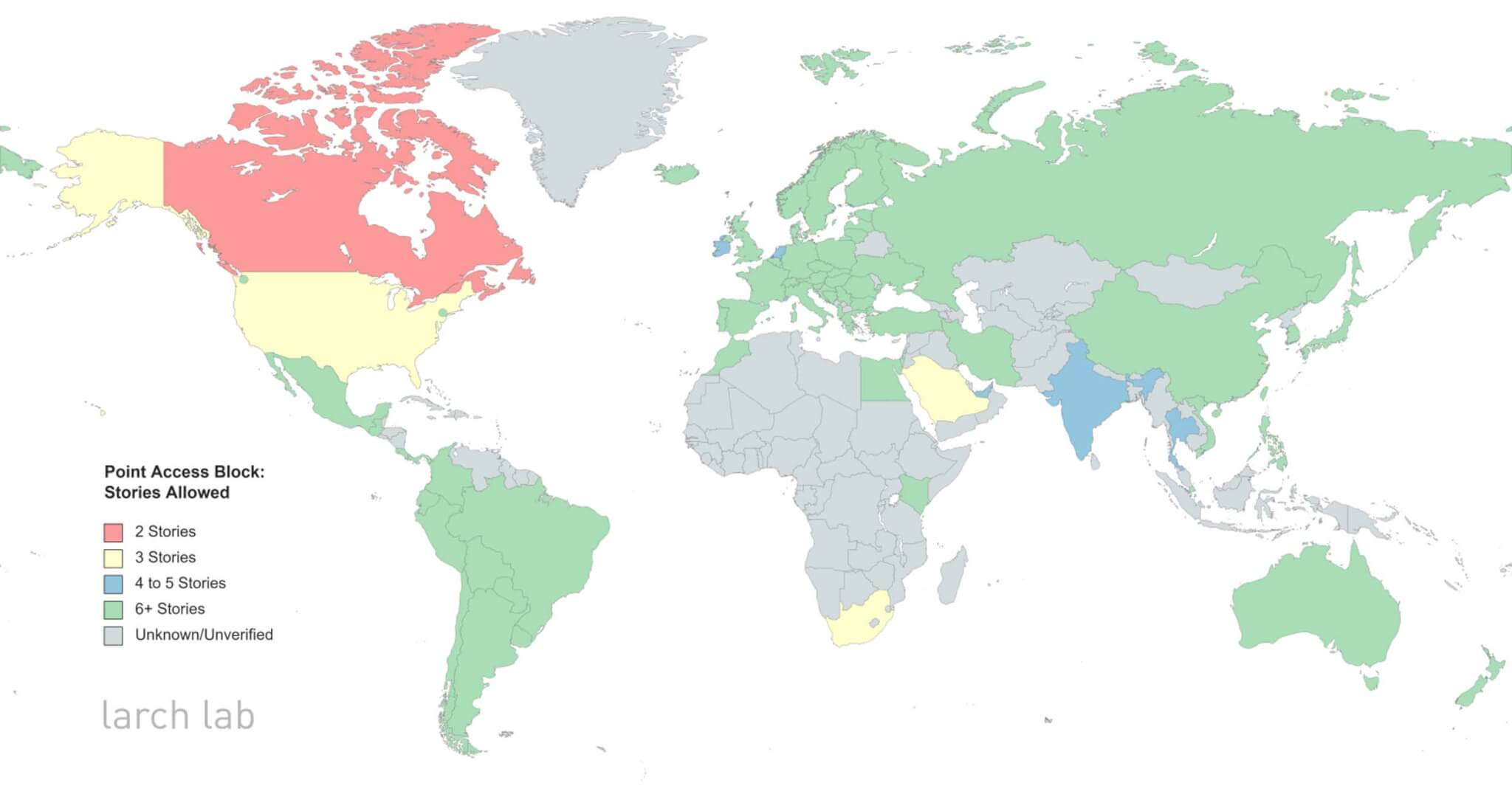

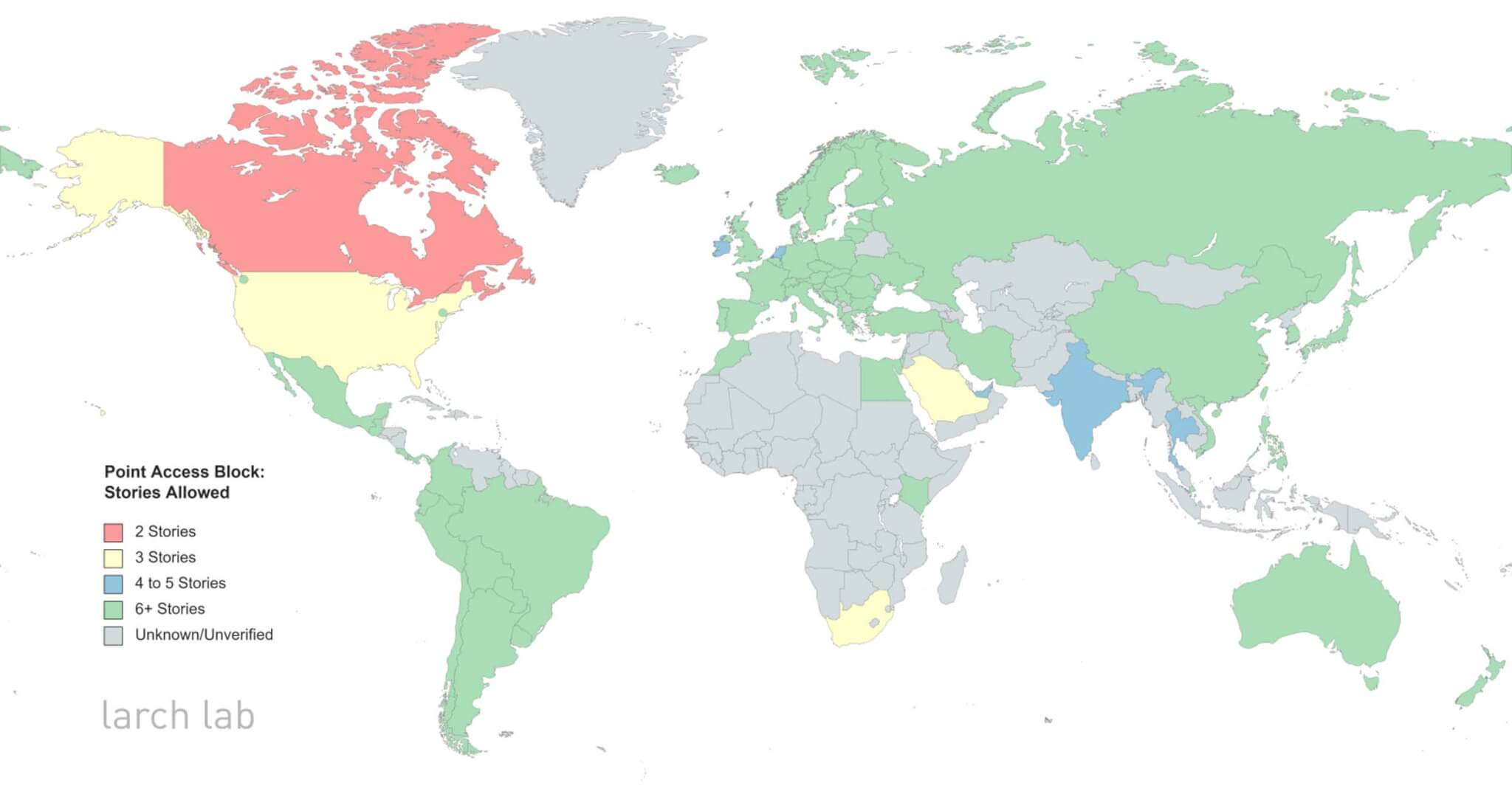

More specifically, it is the peculiar anomaly that requires multifamily buildings to include a second staircase with a connecting corridor for buildings with more than 3 stories. Outside of the U.S. and Canada, this requirement is largely non-existent. It is this regulation that causes our multifamily housing to vary dramatically from the rest of the world. It results in significantly larger buildings with units that are less livable, less climate adaptive, less family friendly, less community-oriented—and potentially much more expensive—than most other countries.

Mapping Point Access Block allowances worldwide (Courtesy Larch Lab)

I’ve been fortunate to work in both the U.S. and Germany during in my career as an architect. This has necessitated navigating building regulations in multiple countries and languages. One of the things that immediately stood out was that the typical multifamily layout in the U.S.—a double loaded corridor, or hotel-like plan with a corridor down the middle and units on either side—was incredibly rare in Europe, largely reserved for student and worker housing. The overwhelming majority of projects were buildings with just a single stair, or, as I have taken to calling them, Point Access Blocks. These buildings—low- and midrise, single-stair buildings either freestanding or connected in series—are ubiquitous from Adelaide to Zürich.

As I started researching floor plans and building regulations in other countries, I realized that most were similar to Germany’s, and none were like ours. There are of course differences: The allowed number of units served by a single stair, the number of floors, whether units opened directly into the stairway or not. However, almost universally, single-stair buildings were the norm. It should be noted that single stair doesn’t necessarily mean one means of egress; Germany’s building codes recognize fire department rescue from an aerial apparatus as a secondary means.

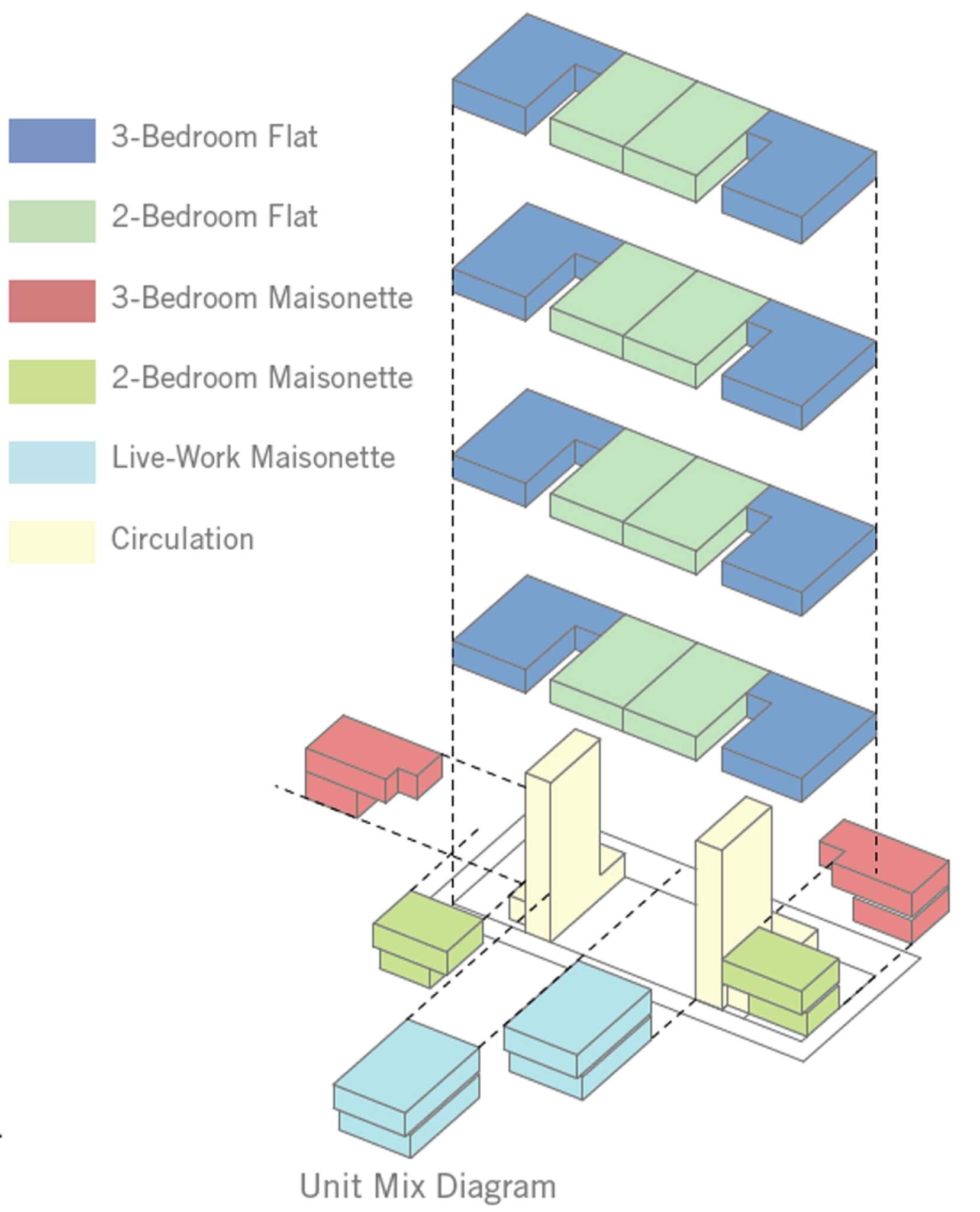

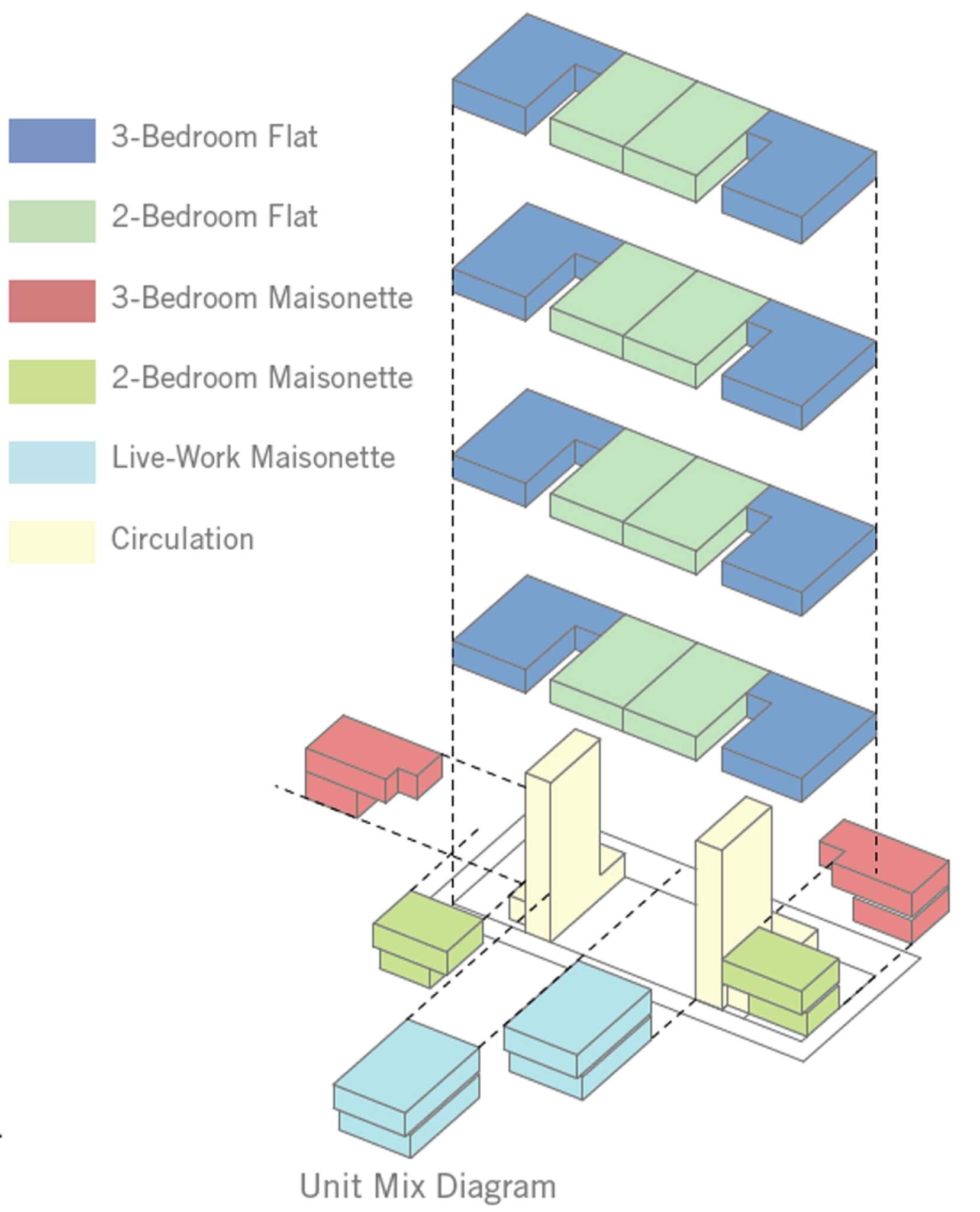

Exploded diagram of [6 story, 22 unit] Point Access Block (Courtesy Larch Lab)

Point Access Blocks are already allowed under the International Building Code [my added comment: IBC Table 1006.3.3(1)], and the Washington State Building Code allows them up to 3 stories above grade. However, Seattle modified its version of the code, allowing Point Access Blocks up to 6 stories (previously there was no height limit), and has permitted them for nearly 50 years. In order to do this, planners must meet numerous conditions including sprinklers, limitations on travel distance, fire-rated doors and assemblies, and corridors separating units and stairways.

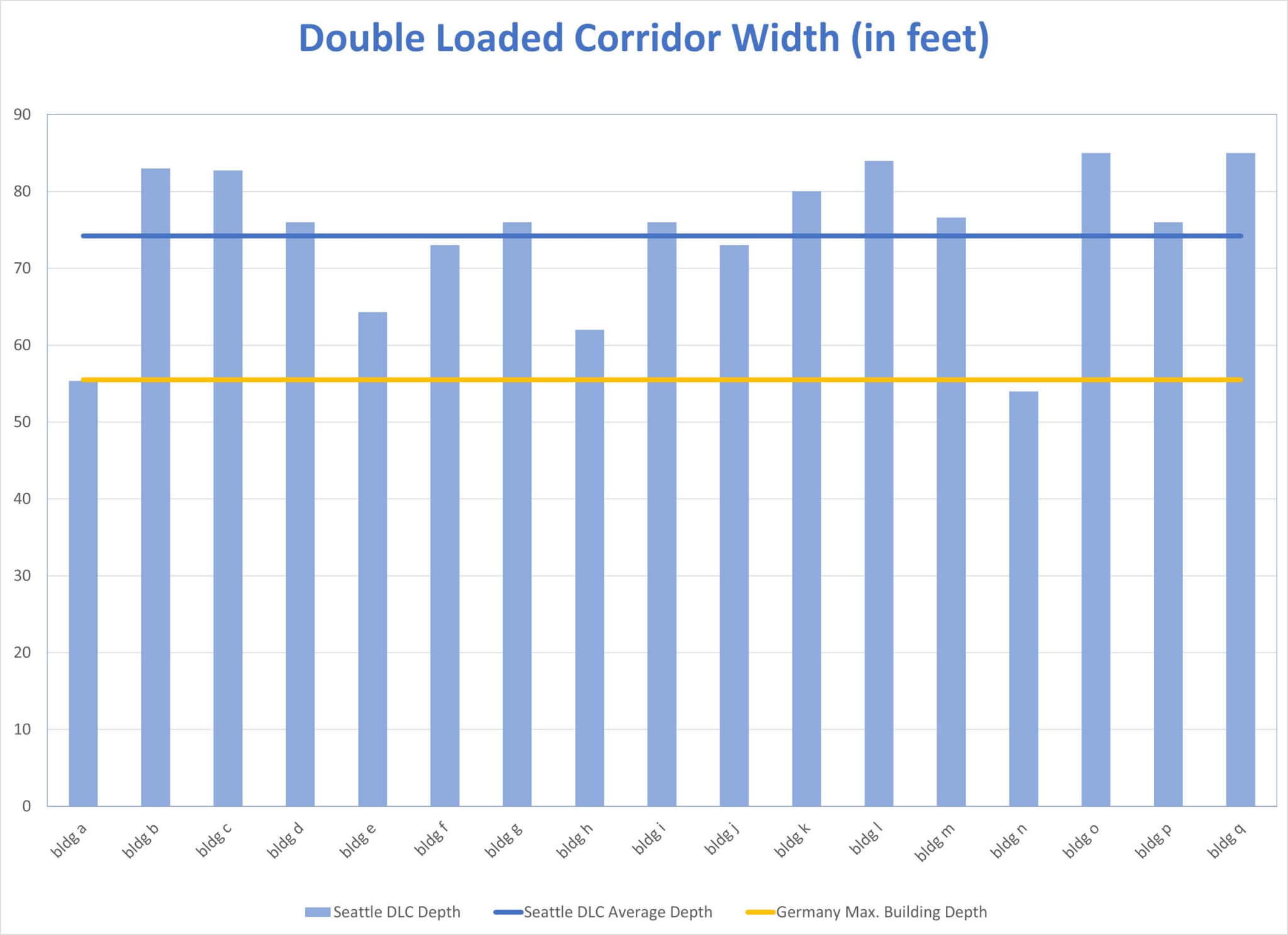

However, for the rest of the U.S., in buildings with more than 4 floors or more than four units per floor, a second stairway and corridor are required. Developers need to hit about 85 to 90 percent floor plate efficiency to be viable (meaning, the leasable or saleable floor area, divided by total floor area), so this mostly results in double-loaded corridor buildings, as the efficiency of single-loaded corridors are typically lower. Plus, FAR is used much more liberally than in other countries, as U.S. cities generally allow nearly double the amount of buildable floor area compared to peer cities in the E.U. Point Access Blocks can hit floor plate efficiencies of up to 95 percent.

The more I researched, the more I realized this one issue was like the Higgs boson of housing. It connects everything. Point Access Blocks unlock small- and medium-sized lots without the need for parcel assemblage and associated cost and time increases. They enable better redevelopment of areas previously zoned single family, allowing for larger and better homes than the typical 1-bedrooms and studios found in double loaded corridors due to existing site constraints and setbacks. Ironically, it is the limitation on the number of units that induces these larger, family-sized units. When strung together in series, connected Point Access Blocks even allow for larger development, including perimeter blocks, but with significantly larger courtyards versus America’s double-loaded corridors. There are countless examples of how to realize these projects in humane ways.

With Point Access Blocks, cross ventilation of units suddenly becomes possible. A recent study looking at effects of various measures to reduce overheating in apartments showed that cross ventilation was the most effective; it can reduce cooling costs by up to 80 percent. The issue of climate adaptation in the built environment is foundational to my firm, Larch Lab. In a warming world, where events like the Pacific Northwest’s recent deadly heat dome or heat-induced power outages become more common, passive survivability must become widespread.

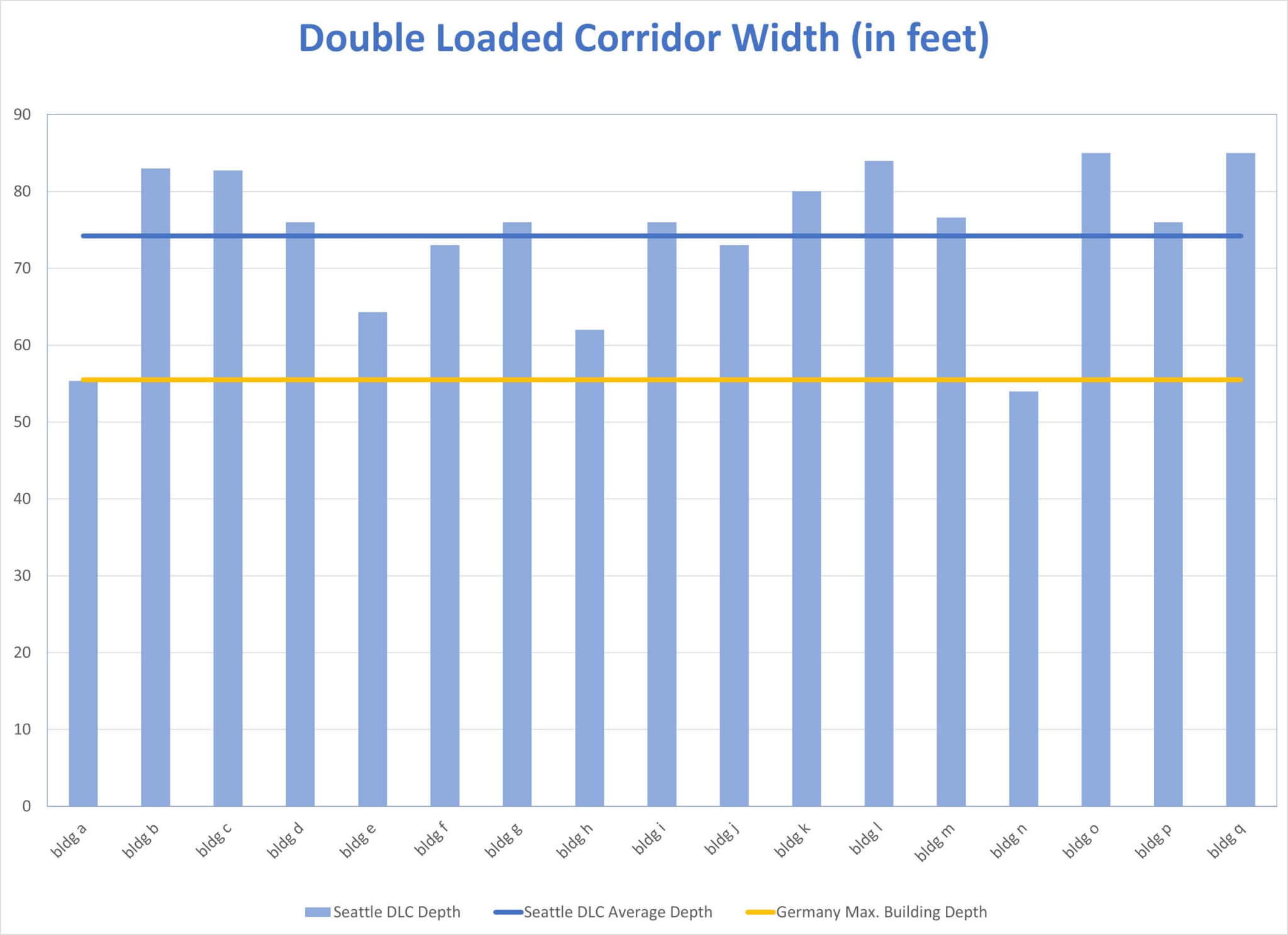

Building depth in Seattle compared to Germany (Courtesy Larch Lab)

[Conclusion of article in next post]

*

Introducing Point Access Blocks

Why does American multifamily architecture look so banal? Here’s one reason

By Michael Eliason • March 29, 2023 • Architecture, Editor's Picks, Letter to the Editor, National, Op-Ed

(Sundry Photography/Shutterstock)

In a recent article in The New York Times, Anna Kodé lamented the blandness of multifamily architecture in the U.S. and posited several theories for this disappointment.

The root cause of the banality is quite simple. The answer is something that, once seen, cannot be unseen: stairs.

More specifically, it is the peculiar anomaly that requires multifamily buildings to include a second staircase with a connecting corridor for buildings with more than 3 stories. Outside of the U.S. and Canada, this requirement is largely non-existent. It is this regulation that causes our multifamily housing to vary dramatically from the rest of the world. It results in significantly larger buildings with units that are less livable, less climate adaptive, less family friendly, less community-oriented—and potentially much more expensive—than most other countries.

Mapping Point Access Block allowances worldwide (Courtesy Larch Lab)

I’ve been fortunate to work in both the U.S. and Germany during in my career as an architect. This has necessitated navigating building regulations in multiple countries and languages. One of the things that immediately stood out was that the typical multifamily layout in the U.S.—a double loaded corridor, or hotel-like plan with a corridor down the middle and units on either side—was incredibly rare in Europe, largely reserved for student and worker housing. The overwhelming majority of projects were buildings with just a single stair, or, as I have taken to calling them, Point Access Blocks. These buildings—low- and midrise, single-stair buildings either freestanding or connected in series—are ubiquitous from Adelaide to Zürich.

As I started researching floor plans and building regulations in other countries, I realized that most were similar to Germany’s, and none were like ours. There are of course differences: The allowed number of units served by a single stair, the number of floors, whether units opened directly into the stairway or not. However, almost universally, single-stair buildings were the norm. It should be noted that single stair doesn’t necessarily mean one means of egress; Germany’s building codes recognize fire department rescue from an aerial apparatus as a secondary means.

Exploded diagram of [6 story, 22 unit] Point Access Block (Courtesy Larch Lab)

Point Access Blocks are already allowed under the International Building Code [my added comment: IBC Table 1006.3.3(1)], and the Washington State Building Code allows them up to 3 stories above grade. However, Seattle modified its version of the code, allowing Point Access Blocks up to 6 stories (previously there was no height limit), and has permitted them for nearly 50 years. In order to do this, planners must meet numerous conditions including sprinklers, limitations on travel distance, fire-rated doors and assemblies, and corridors separating units and stairways.

However, for the rest of the U.S., in buildings with more than 4 floors or more than four units per floor, a second stairway and corridor are required. Developers need to hit about 85 to 90 percent floor plate efficiency to be viable (meaning, the leasable or saleable floor area, divided by total floor area), so this mostly results in double-loaded corridor buildings, as the efficiency of single-loaded corridors are typically lower. Plus, FAR is used much more liberally than in other countries, as U.S. cities generally allow nearly double the amount of buildable floor area compared to peer cities in the E.U. Point Access Blocks can hit floor plate efficiencies of up to 95 percent.

The more I researched, the more I realized this one issue was like the Higgs boson of housing. It connects everything. Point Access Blocks unlock small- and medium-sized lots without the need for parcel assemblage and associated cost and time increases. They enable better redevelopment of areas previously zoned single family, allowing for larger and better homes than the typical 1-bedrooms and studios found in double loaded corridors due to existing site constraints and setbacks. Ironically, it is the limitation on the number of units that induces these larger, family-sized units. When strung together in series, connected Point Access Blocks even allow for larger development, including perimeter blocks, but with significantly larger courtyards versus America’s double-loaded corridors. There are countless examples of how to realize these projects in humane ways.

With Point Access Blocks, cross ventilation of units suddenly becomes possible. A recent study looking at effects of various measures to reduce overheating in apartments showed that cross ventilation was the most effective; it can reduce cooling costs by up to 80 percent. The issue of climate adaptation in the built environment is foundational to my firm, Larch Lab. In a warming world, where events like the Pacific Northwest’s recent deadly heat dome or heat-induced power outages become more common, passive survivability must become widespread.

Building depth in Seattle compared to Germany (Courtesy Larch Lab)

[Conclusion of article in next post]

Last edited: