Yikes

SAWHORSE

https://calmatters.org/housing/2025/05/building-code-california-housing/

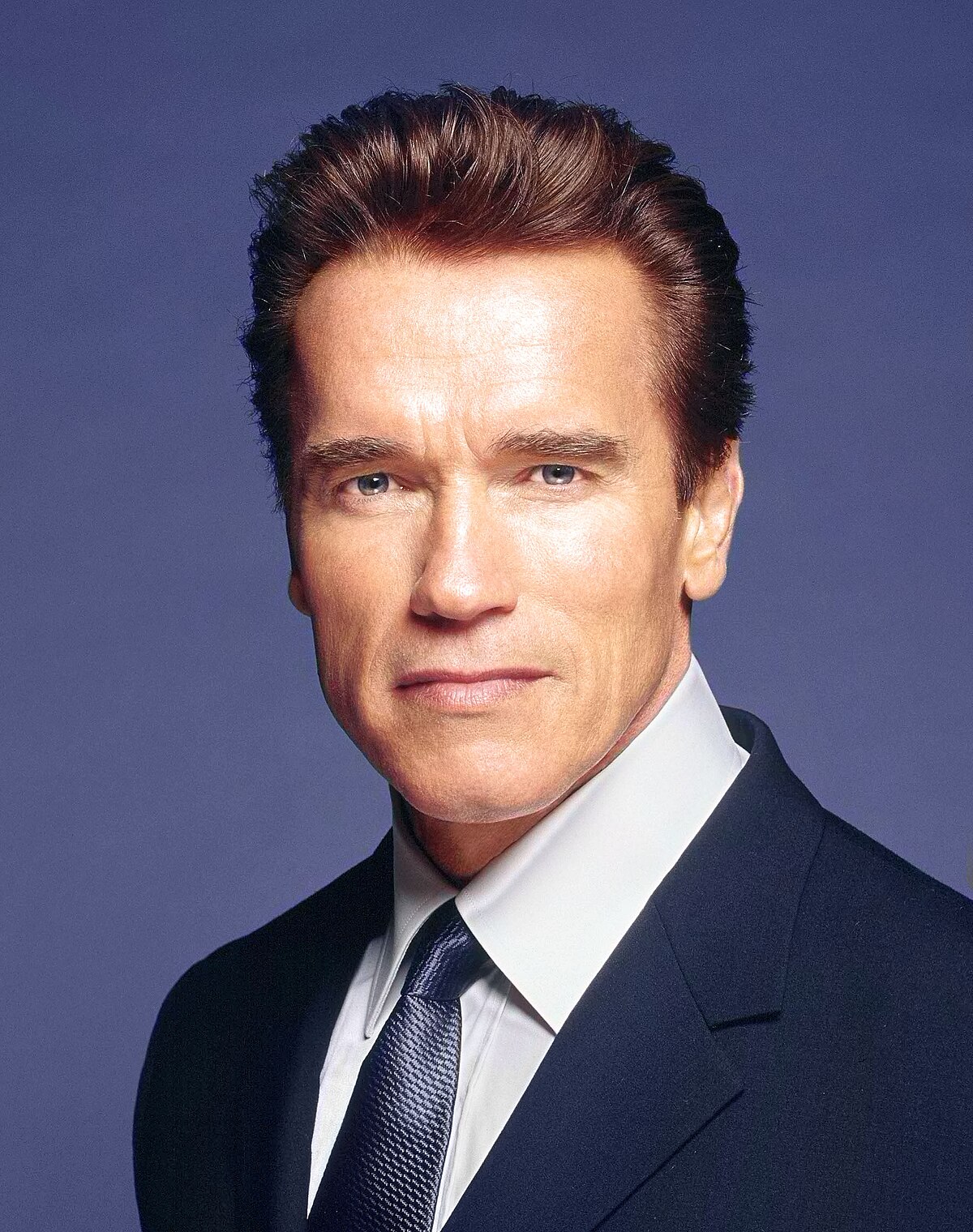

New homes under construction in Pleasanton on June 16, 2024. The city of Pleasanton has voted to explore the possibility of becoming a charter city.

Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

As lawmakers scramble to turbocharge post-fire recovery efforts in Los Angeles and to tackle a housing shortage across the state, a new addition may be coming to California’s building code: A pause button.

Assembly Bill 306 would freeze the building standards — the rules governing the architecture, the layout, the electrical wiring, the plumbing, the energy use and the fire and earthquake safety features — for all new housing through at least 2031. Local governments, which often tack on their own requirements, would also be kept from doing so in most cases.

Building standards tend to reflect the state’s most pressing concerns. New seismic requirements are added after major earthquakes, home-hardening requirements have followed deadly fires and new green energy mandates have popped up as California has raced to prepare for a warmer planet.

This latest proposed change to the code is meant to tackle another crisis: affordability.

The bill wouldn’t delete any of the current rules, which are widely considered to be among the most stringent of any state’s. It would also include exceptions, most notably for emergency health and safety updates. But on the whole, the California building code would be set on cruise control for the better half of a decade.

Assemblymember Nick Schultz, a freshman Democrat from Burbank and the lead author of the bill, said there’s nothing extreme about leaving the code as it is for a few years, particularly as homeowners in Altadena and the Palisades rebuild.

Though Schultz introduced the bill, the second listed co-author may explain why such a significant policy change swept through the Assembly with little resistance: Speaker Robert Rivas. In early April the bill passed out of the Assembly with 71 “yes” votes. No lawmakers voted against it. Now it heads to the state Senate.

Such smooth legislative sailing notwithstanding, plenty of environmental advocates, renewable energy industry groups, construction unions, structural engineers and code enforcement officials have turned out to oppose the bill. They see it as a radical upending of the way the state regulates buildings, reduces emissions and prepares for a changed climate.

Building standards need to be nimble because the effects of climate change are unpredictable, said Laura Walsh, policy manager with Save the Bay, a nonprofit focused on conservation and preparing for rising seas.

“We’ll get to a place in the trend where things get worse really fast,” she said.

Beyond the specifics of the debate, the bill represents something fairly new in the politics of California housing.

Over the last decade, lawmakers in Sacramento have passed a raft of bills aimed at making it easier to build new homes. Most of those bills have set their sights on the zoning code — the patchwork of land-use standards that dictate which types of buildings can go where. If you recall any high-profile political battles about apartment buildings in exclusive suburbs, dense residential development near transit stops or proposed mountain lion sanctuaries — that’s all about zoning.

Now some lawmakers are considering a new deregulatory target. Schultz’s freeze is the most dramatic example of a handful of bills this year that would take on the impenetrably technical, frequently overlooked and ever-changing building code — all for the cause of cheaper housing.

As California legislators are “finding religion on land use, other issues are sort of bubbling up,” said Stephen Smith, founder of the Center for Building in North America, a nonprofit that advocates for changes to building codes that make it easier to build apartment buildings. “Architects, developers, contractors are pointing out, ‘No, actually, there are barriers in the actual construction process and many of those do go back to the building code.’”

As with most states, our code takes as its jumping off point a set of general rules written by the International Code Council, a nonprofit organization governed by a mix of building industry associations, state and local regulators, engineers and architects. Despite the name, the organization is based in Washington D.C. and its model codes are a predominantly North American product.

“It’s like naming the World Series the World Series,” said Eduardo Mendoza, a research associate with California YIMBY, an organization that promotes more housing development.

The Code Council puts out its model codes every three years. The state then gets to work on its own version in a year-long process involving seven state departments.

These exceedingly arcane deliberations typically receive little attention from the public. The exception is a small cadre of engineers, developers, architects, appliance manufacturers, energy efficiency, solar and climate advocates and other parties with a direct financial or ideological interest in the way new things get built.

For these groups, the triannual code adoption cycle — and the “intervening” amendment process for urgent updates — make for an endless game of regulatory tug-of-war.

“It’s all very bureaucratic, very dry, but still extremely political,” said Mendoza.

Now that behind-the-scenes fight is playing out in public.

On one side are housing developers. Keeping up with the salvo of state and local building code changes is its own full-time job, said Dan Dunmoyer, president of the California Building Industry Association, a trade group for big builders.

“We had the most seismically safe, water-reduced, fire retardant, energy efficient homes in the world two years ago and we just keep on adding more and more and more to it,” he said. “At what point do you just take a pause?”

A potential pause is especially appealing to many affordable housing developers, who typically rely on multiple sources of funding, all with their own restrictions and timelines. If a change in the building code means going back to the architectural drawing board and delaying a permit application, that can put off a potential project “another year or two,” said Laura Archuleta, president of Jamboree Housing Corporation, a nonprofit low-income housing developer in Irvine.

California would not be the first state to consider tapping the brakes on its building code. In 2023, legislators in North Carolina passed a law banning most changes through 2031. That bill, backed by that state’s building industry association, froze in place a significantly older code than California’s; some of North Carolina’s energy efficiency rules hadn’t been changed since 2009.

California’s so-called 2025 code is set to go into effect in January 2026. That change will be grandfathered in, even if Schultz’s measure passes. No additional changes would allowed until June 1, 2031.

The experts who help write the state’s building standards have “health and safety and other criteria in mind but they don’t have cost as a factor in their decision making — well, they should,” said Assemblymember Chris Ward, a San Diego Democrat who voted for Schultz’s bill. He is also the author of two other building code related bills this year. One would require the state to consider subjecting small apartment buildings to a more relaxed set of standards. The other would reevaluate whether builder should have more flexibility in meeting the state’s energy efficiency rules.

Ward said that mining the building code for possible cost savings is an idea embraced by a growing number of his colleagues.

“The theme of the year has been ‘let’s all focus in on the cost of construction and on reducing the cost of housing,” he said.

Is the secret to housing affordability in California buried in the building code?

by Ben Christopher May 15, 2025

New homes under construction in Pleasanton on June 16, 2024. The city of Pleasanton has voted to explore the possibility of becoming a charter city.

Photo by Loren Elliott for CalMatters

As lawmakers scramble to turbocharge post-fire recovery efforts in Los Angeles and to tackle a housing shortage across the state, a new addition may be coming to California’s building code: A pause button.

Assembly Bill 306 would freeze the building standards — the rules governing the architecture, the layout, the electrical wiring, the plumbing, the energy use and the fire and earthquake safety features — for all new housing through at least 2031. Local governments, which often tack on their own requirements, would also be kept from doing so in most cases.

Building standards tend to reflect the state’s most pressing concerns. New seismic requirements are added after major earthquakes, home-hardening requirements have followed deadly fires and new green energy mandates have popped up as California has raced to prepare for a warmer planet.

This latest proposed change to the code is meant to tackle another crisis: affordability.

The bill wouldn’t delete any of the current rules, which are widely considered to be among the most stringent of any state’s. It would also include exceptions, most notably for emergency health and safety updates. But on the whole, the California building code would be set on cruise control for the better half of a decade.

Assemblymember Nick Schultz, a freshman Democrat from Burbank and the lead author of the bill, said there’s nothing extreme about leaving the code as it is for a few years, particularly as homeowners in Altadena and the Palisades rebuild.

Though Schultz introduced the bill, the second listed co-author may explain why such a significant policy change swept through the Assembly with little resistance: Speaker Robert Rivas. In early April the bill passed out of the Assembly with 71 “yes” votes. No lawmakers voted against it. Now it heads to the state Senate.

Such smooth legislative sailing notwithstanding, plenty of environmental advocates, renewable energy industry groups, construction unions, structural engineers and code enforcement officials have turned out to oppose the bill. They see it as a radical upending of the way the state regulates buildings, reduces emissions and prepares for a changed climate.

Building standards need to be nimble because the effects of climate change are unpredictable, said Laura Walsh, policy manager with Save the Bay, a nonprofit focused on conservation and preparing for rising seas.

“We’ll get to a place in the trend where things get worse really fast,” she said.

Beyond the specifics of the debate, the bill represents something fairly new in the politics of California housing.

Over the last decade, lawmakers in Sacramento have passed a raft of bills aimed at making it easier to build new homes. Most of those bills have set their sights on the zoning code — the patchwork of land-use standards that dictate which types of buildings can go where. If you recall any high-profile political battles about apartment buildings in exclusive suburbs, dense residential development near transit stops or proposed mountain lion sanctuaries — that’s all about zoning.

Now some lawmakers are considering a new deregulatory target. Schultz’s freeze is the most dramatic example of a handful of bills this year that would take on the impenetrably technical, frequently overlooked and ever-changing building code — all for the cause of cheaper housing.

As California legislators are “finding religion on land use, other issues are sort of bubbling up,” said Stephen Smith, founder of the Center for Building in North America, a nonprofit that advocates for changes to building codes that make it easier to build apartment buildings. “Architects, developers, contractors are pointing out, ‘No, actually, there are barriers in the actual construction process and many of those do go back to the building code.’”

Where does the building code come from?

California’s building code does not originate in California.As with most states, our code takes as its jumping off point a set of general rules written by the International Code Council, a nonprofit organization governed by a mix of building industry associations, state and local regulators, engineers and architects. Despite the name, the organization is based in Washington D.C. and its model codes are a predominantly North American product.

“It’s like naming the World Series the World Series,” said Eduardo Mendoza, a research associate with California YIMBY, an organization that promotes more housing development.

The Code Council puts out its model codes every three years. The state then gets to work on its own version in a year-long process involving seven state departments.

These exceedingly arcane deliberations typically receive little attention from the public. The exception is a small cadre of engineers, developers, architects, appliance manufacturers, energy efficiency, solar and climate advocates and other parties with a direct financial or ideological interest in the way new things get built.

For these groups, the triannual code adoption cycle — and the “intervening” amendment process for urgent updates — make for an endless game of regulatory tug-of-war.

“It’s all very bureaucratic, very dry, but still extremely political,” said Mendoza.

Now that behind-the-scenes fight is playing out in public.

On one side are housing developers. Keeping up with the salvo of state and local building code changes is its own full-time job, said Dan Dunmoyer, president of the California Building Industry Association, a trade group for big builders.

“We had the most seismically safe, water-reduced, fire retardant, energy efficient homes in the world two years ago and we just keep on adding more and more and more to it,” he said. “At what point do you just take a pause?”

A potential pause is especially appealing to many affordable housing developers, who typically rely on multiple sources of funding, all with their own restrictions and timelines. If a change in the building code means going back to the architectural drawing board and delaying a permit application, that can put off a potential project “another year or two,” said Laura Archuleta, president of Jamboree Housing Corporation, a nonprofit low-income housing developer in Irvine.

California would not be the first state to consider tapping the brakes on its building code. In 2023, legislators in North Carolina passed a law banning most changes through 2031. That bill, backed by that state’s building industry association, froze in place a significantly older code than California’s; some of North Carolina’s energy efficiency rules hadn’t been changed since 2009.

California’s so-called 2025 code is set to go into effect in January 2026. That change will be grandfathered in, even if Schultz’s measure passes. No additional changes would allowed until June 1, 2031.

The experts who help write the state’s building standards have “health and safety and other criteria in mind but they don’t have cost as a factor in their decision making — well, they should,” said Assemblymember Chris Ward, a San Diego Democrat who voted for Schultz’s bill. He is also the author of two other building code related bills this year. One would require the state to consider subjecting small apartment buildings to a more relaxed set of standards. The other would reevaluate whether builder should have more flexibility in meeting the state’s energy efficiency rules.

Ward said that mining the building code for possible cost savings is an idea embraced by a growing number of his colleagues.

“The theme of the year has been ‘let’s all focus in on the cost of construction and on reducing the cost of housing,” he said.