Before PDFs, digital submittals, and cloud-based plan portals, we had real blueprints—chemically treated sheets that turned deep blue with white lines. Anyone who’s been in this business long enough remembers the smell of ammonia from a diazo machine or the feel of those oversized, curled-up rolls. But what most people don’t realize is that blueprints weren’t just about showing what to build; they were created to control what was being built and to keep everyone honest.

The Early Days: Linen, Ink, and Creative Control

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, architects and engineers drafted plans by hand using India ink on linen or vellum. These were durable materials that held up better than paper. But they were one-offs. The “original” was it. If someone wanted to build off that, they had to either trace it or redraw it entirely.And that’s where things went sideways.

Before blueprints became the standard, the architect often held all the cards. Daniel Burnham, the renowned Chicago architect behind the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, was known for quietly editing other architects’ plans. If he didn’t like a design element, he’d take the drawing, make changes to it on his own time, and then slip it back into the process. No warning, no sign-off, and no real way to track it. This wasn’t unique to Burnham; it was the norm. If you had the only copy, you controlled the project.

Cyanotype Changes Everything

Then came the blueprint. The cyanotype process was developed in the 1840s and adapted for architectural use in the decades that followed. Drawings on translucent linen or tracing cloth could be placed over light-sensitive paper and exposed to sunlight. Where the light passed through, it triggered a chemical reaction that turned the sheet blue. Where the ink blocked the light, white lines remained. The result was a cheap, reliable duplicate that preserved every detail of the original.Now contractors, trades, inspectors, and builders could all work from the same document. It created accountability. You could roll into court with a print and prove exactly what was supposed to be built. Changes had to be reissued. Revisions had to be tracked. Blueprints brought order to the chaos.

From Artist to Coordinator

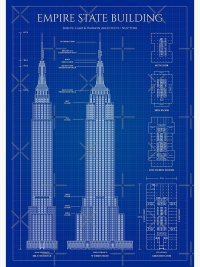

Before blueprints, the architect was often seen as more of a visionary—a creative mind with a pencil and a sketchpad. But when blueprints took over, the role evolved. Now the architect wasn’t just designing; they were coordinating. They had to produce clear, detailed documents that electricians, masons, and framers could actually build from. The drawing set became a legal record, not just an artistic suggestion.Compare the past to today and you’ll see just how far things have gone. The Empire State Building was constructed in 1930 and only required about 100 sheets of drawings. Today, that same structure would likely require thousands of sheets, broken into disciplines, with revision logs, cross-references, and callouts on every page. The expectations shifted, and so did the responsibility.

Sears and the Democratization of Construction

Blueprints didn’t just change commercial buildings; they helped bring construction to the everyday American. In 1908, Sears, Roebuck & Co. launched its Modern Homes program. You could order a house from the Sears catalog, and a boxcar would show up with all the precut lumber, windows, nails, doors, and a complete set of blueprints. That’s how a regular person could build a home, because the plans told them exactly how to do it.Over the next three decades, Sears offered over 370 different designs and shipped out more than 70,000 homes. The blueprints were critical. They standardized the process, ensured quality, and eliminated guesswork. If Sears could put together a house kit that worked across the country, it was because the drawings were clear enough for anyone to follow.

Why This Still Matters

Even though we don’t use chemically developed blueprints anymore, the principles behind them haven’t changed. We still need control. We still need coordination. We still need to know that what’s on the drawing is what’s in the field. Whether it’s a stamped PDF or a full-size plot, the purpose is the same: clarity, accountability, and a shared understanding of what is being built.So the next time someone tosses around the word “blueprint” without thinking, remember this: that word came from a time when drawings were burned into paper with sunlight and washed in water. When one drawing could make or break a project. And when printing a second copy meant locking in the truth for everyone to see.